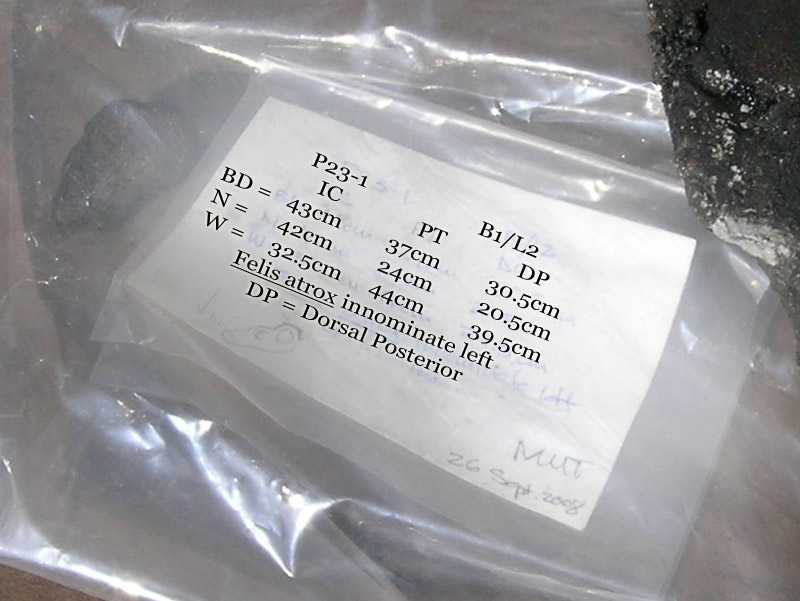

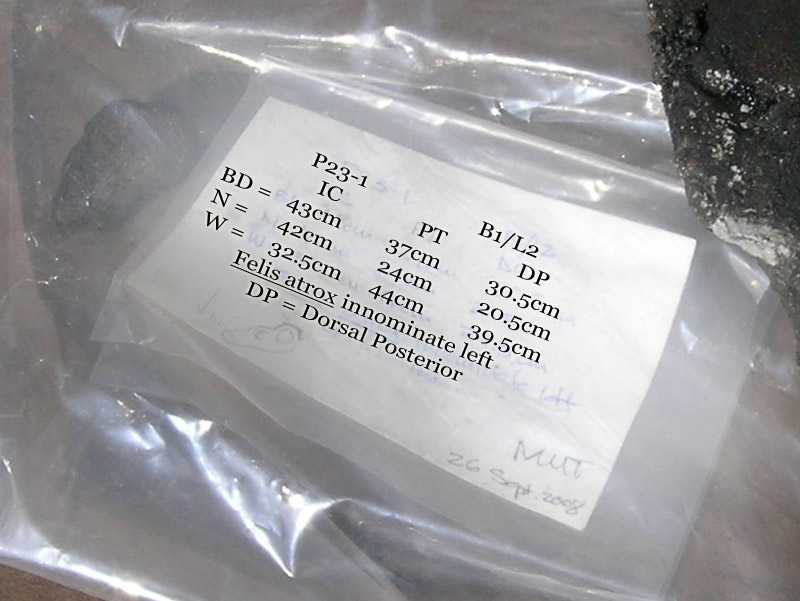

Earlier this week, we measured out the left half of an American Lion pelvis (or, more anatomically correctly, an innominate). Whilst typing this into yesterday's entry, I realized I've never actually explained what "measuring" a fossil entails, let alone why we do it.

"Measuring out" a fossil means recording the location of two to three of the bone's anatomical points (usually three) within the context of a 1m x 1m x 25cm grid. For instance, take our most recent innominate:

The three dots and abbreviations above represent the three different anatomical points: IC stands for Illiac Crest; PT means Pubic Tubercle, and DP means Dorsal Posterior (which isn't actually a point -- it's a general orientation. This portion of the bone is broken off, so there isn't an actual feature to measure. Instead, we measure an arbitrary point, and name it after the point's location in the body: Dorsal, or toward the spine, and Posterior, or toward the rear end).

Each of these three points gets three pieces of data of their very own: measurements of the fossil's location below the original surface of the deposit (abbreviated as "BD" for "Below Datum"), north of the southern most line of the grid (N), and west of the easternmost line of the grid (W). These measurements are written into our field notes, and carbon copied (literally, with little blue pieces of carbon paper) onto 3" x 5" cards. Confused yet? Fear not, it sounds much more complicated than it actually is. But here's an enhanced version of the final product:

Remember Algebra class waaaay back in 9th grade? Wait, let me rephrase that -- remember any of the

math from Algebra class waaaay back in 9th grade? Yeah, me neither. However, had you paid closer attention to the

graphing portion of your text (and less attention to Spitball Trajectory 101), you would recognize those three columns of numbers as

coordinates within a 3-dimensional graph. For example, for the IC, x = 43, y = 42, z = 32.5, etc. By recording all of these coordinates, we're able to later reconstruct the fossil's position within the deposit. And in doing that, we can learn all sorts of nifty things about how skeletons fall apart within a tar pit, or which animal got trapped first, or how asphaltic sand shifts underground over time, and so on and so forth.

A better photo narrative of a fossil's journey from grubby, dirt-covered groundling to a finished, fully prepared specimen is forthcoming, but until then, I hope this has been helpful. Or, at the very least, has inspired you all to pay closer attention in Algebra II.